Legislative complexity: what is it, how do we measure it, and why does it matter?

Lisa Burton Crawford, Elma Akand, Steefan Contractor and Scott Sisson

23.11.2022

The ongoing inquiry of the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) into Financial Services Legislation has cast new light on the complexity of legislation enacted by the Australian Parliament. As the ALRC explained in its first interim report:

The Inquiry is set against the background of the Australian Government’s response to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry and, in particular, the Government’s acceptance of the Royal Commission’s call for simplification of the law so that its intent is met. The Royal Commission emphasised in its Final Report that the ‘more complicated the law, the harder it is to see unifying and informing principles and purposes’.

This post aims to harness some of the ‘significant appetite and impetus for change’ that the ALRC identified with respect to federal financial services legislation (ARLC, Summary Report B, 4) for the broader phenomenon legislative complexity — which, we argue, has become systemic. This is demonstrated by data that we collected from the Federal Register of Legislation (FRL).

Measuring legislative complexity

Defining complexity is itself a complex task. When we say legislation is complex, we mean that it is complicated, or in other words, that it is difficult to read and understand. This post presents initial data on two potential measures of complexity: volume of legislation, and rate of change.

Some might think that volume of legislation is a crude measure of complexity. But it is important because, pending radical technology advances, legislation has to be read by people (including the members of Parliament who pass the legislation, those subject to the legislation, executive decision-makers and judges) in order to have an effect in the real world. And people have limited time, attention and powers of recall. As the Canadian scholar Vincent Chiao explained it, the sheer volume of legislation ‘swamps’ the ability of people to find the relevant pieces of legislation, and read and understand it when they do.

Rate of change is another important indicator of complexity. The frequent amendment of legislation compounds the challenge outlined above: if legislative texts change rapidly, more time and effort is required to identify the current law. As Fuller explained, we would not want laws to stand still, but ‘legislative inconstancy’ thwarts people to plan their lives within the framework of the law.

The data presented in this piece is part of a collaborative attempt to apply some of the empirical methods that one of us previously used to analyse Australian legislation on a larger scale. Given the difficulty in collecting and analysing this data, we analysed a sample of 20 federal statutes, chosen because they represented a wide range of subject matters and were enacted across several decades. It was hoped that this sample would give us an insight into system-wide trends and avoid subject-matter specific distortions.

Our sample included three Acts which are notoriously complex — the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA 36), Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 97) and the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act) — to provide some points of comparison. But we included a range of other Acts that have received comparatively little attention, such as the Aged Care Act 1997 (Aged Care Act), Customs Act 1901 (Customs Act), Native Title Act 1993 and the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. The data presented below is accurate, to the best of our knowledge, as of 18 October 2022.

Volume of legislation

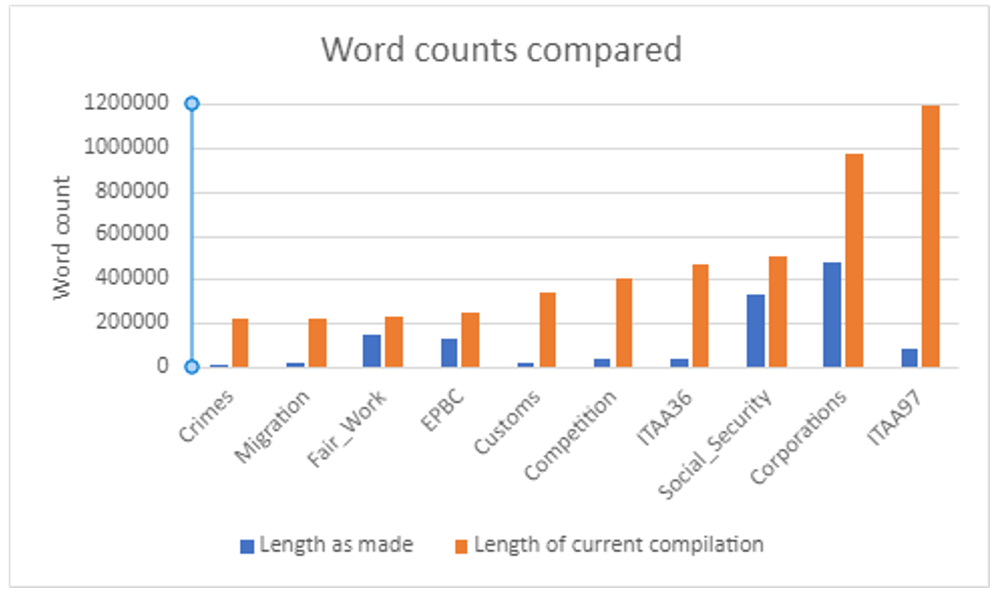

There is no straightforward way to measure the total volume of primary legislation now in force in Australia. For one, there is no compilation of all the legislation now in force (like there is in the US). The FRL and Austlii both provide free public access to all of the legislation now in force. However, extracting data from the FRL is a laborious process and often runs into technical roadblocks. For now, we have compared the Acts ‘as enacted’ with the current compilation published by the FRL.

The data was obtained by automated scripts that counted words but omitted certain non-operative components — particularly the ‘endnotes’, which record the amendments which have been made to each Act. We measured word count rather than page numbers to avoid potential distortions, given contemporary legislation is now formatted to include more ‘white space’. The below table and graphs show the respective word counts, and the percentage increase between each.

This data confirms that many federal statutes are, quite simply, very long. The median word count of each of these Acts as made was 46,395 — over half the length of an average PhD thesis in the discipline of law. The size of every Act we measured also grew over time. For some the increase was small (e.g. the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHS Act), but over half of the Acts doubled in length, and more than a quarter recorded more than ten-fold growth. The median word count of each Act is currently 194,558 — almost 2.5 doctoral theses combined. The ITAA97 and Corporations Act are clear outliers (the current version of the ITAA 97 is twice as long as the novel War and Peace). But the Social Security Act 1991 (Social Security Act) is almost as long as Tolstoy’s novel, and the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Competition and Consumer Act) also comes close. We used median measurements here rather than means to minimise the distorting effect of these outliers.

Rate of change

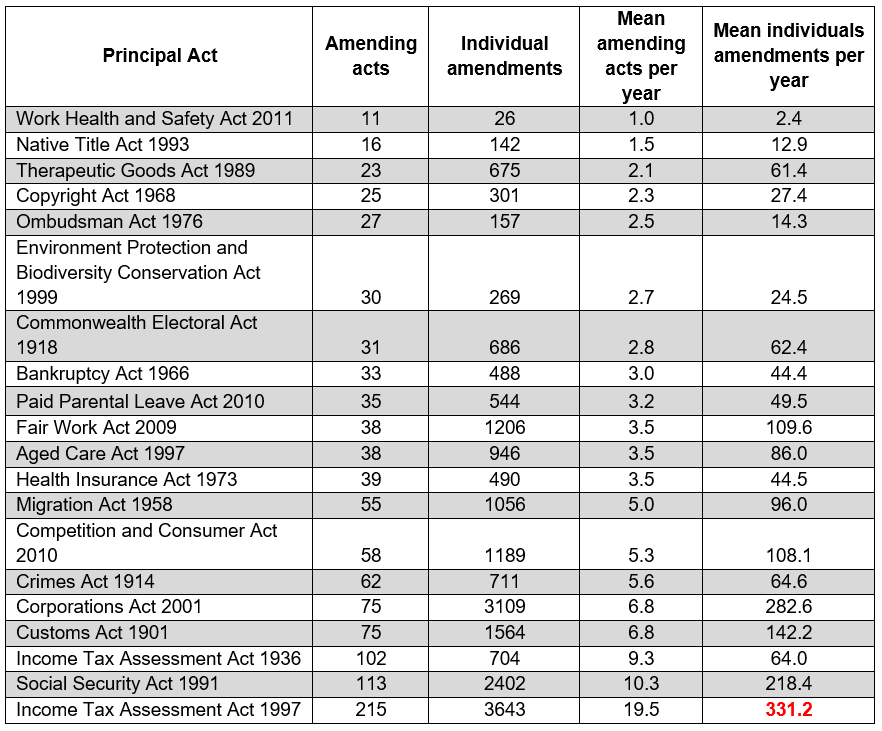

We also measured the number of times each Act had been amended over its entire life span, and in the last complete decade (2011 to 2021). We extracted that data from the amendment history provided in the latest compilation of each Act. We used this to generate means (i.e. averages) to get a rough insight into the frequency of change.

This table presents the data for 2011-2021. ‘Amending Acts’ refers to the number of Acts which were enacted by Parliament during this time frame, which made any number of changes to the Principal Act. ‘Individual Amendments’ refers to the total number of changes made to the Principal Act in this time frame.

This demonstrates that every one of our 20 Acts was amended in this time frame. The WHS ACT was amended the least — but even so, it was changed about once a year. At the other end of the spectrum was the ITAA 97: 3643 individual changes were made to this Act by 215 amending Acts (almost once a fortnight). The Social Security Act, Customs Act, Crimes Act 1914 (Crimes Act), Competition and Consumer Act and Migration Act 1958 were all amended about once every two months.

Averages are an imperfect measure here, because they do not capture the potentially uneven distribution of amendments. For instance, the Social Security Act was amended much more frequently in the first decade after it was enacted than in the years since:

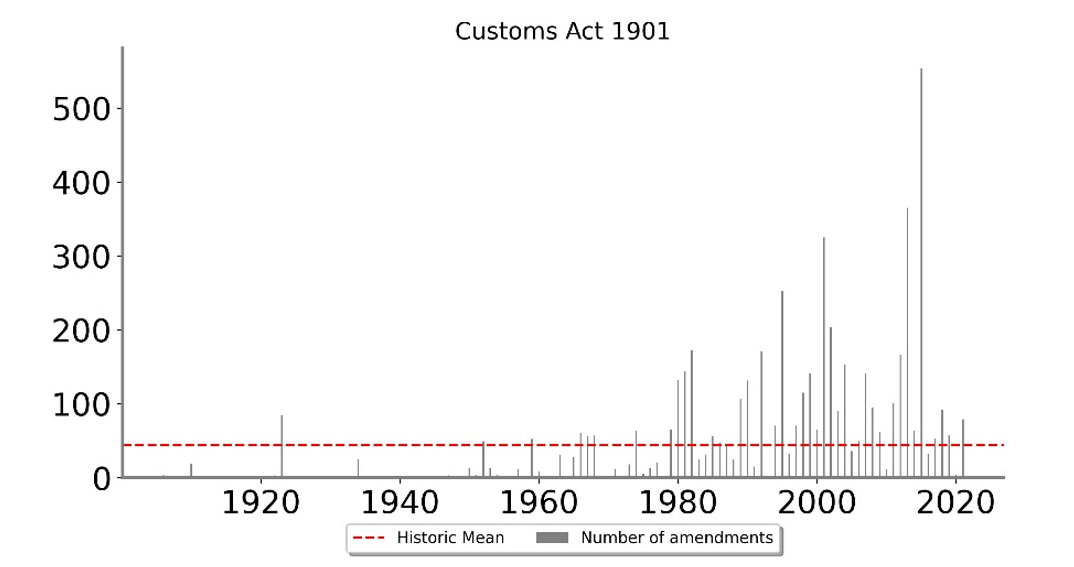

For other Acts, the trend was the reverse — the Crimes Act and Customs Act, for example, were amended much more frequently in recent years:

And for some Acts, amendments were fairly evenly distributed across their lifespan:

We also extracted data about the number of amendments made per amending Act. This gives an indication of the lines of inquiry that data-driven analysis can open up. For example, are there any generalisable trends in frequency of amendment, or does the rate of amendment vary from statute to statute depending on subject-specific concerns? Does Parliament tend to endlessly tinker with its statutes, making small changes here and there, or does it tend instead to enact substantial reforms? This all provides insight into the way that Parliament functions.

Why does this matter?

One of the most valuable contributions made by the ARLC inquiry to date is the huge body of data that it has generated about financial services legislation, and its complexity. Data-driven analysis of legislative complexity is important for (at least) two reasons. The first is to clarify the nature and extent of the phenomenon. People have been commenting on (and criticising) the complexity of legislation for centuries, but it is often not until one sees the figures about just how much legislation there is, and other salient indicators of complexity like how frequently it is amended, that the importance of the issue becomes clear.

The second reason is that data-driven analysis can correct mistaken assumptions about the form of legislation, and the function of the legislature. Many public lawyers appear to assume that the main practical challenge presented by legislation is its indeterminacy; further, that the main constitutional problem posed by that indeterminacy is the enlargement of executive power. (By indeterminacy, we mean legislation that uses vague terms like ‘reasonable’ or ‘fit and proper’, or else confers discretionary powers). That may well be the case in some jurisdictions, like the US. The weight of authority suggests that the legislation enacted by Congress tends to be highly indeterminate, conferring broad, purpose-orientated powers on the executive branch — including the power to make (secondary) legislation of its own. And so, the volume of legislation made by Congress is now utterly swamped by the secondary legislation made by executive agencies. The assumption that this is a universal trend informs the stories that we tell in law school: that statutes set the broad policy agenda, but all the technical detail is left ’to the regs’. It also drives the direction of legal research, which often focuses on the (significant) constitutional issues raised by discretionary executive powers and executive-made law, and Parliament’s ability to control them.

But the data indicate that this is not the way that legislation functions in Australia. Ours does not appear to be a legal system in which the legislature sits back, and leaves matters to the executive branch: the federal Parliament is also very active, enacting huge volumes of legislation that is often rapidly amended. This is not to deny the significance of executive discretion or executive-made law in the Australian legal system. The point is that this is just part of the picture, and that the proliferation of technical primary legislation deserves just as much attention. The next line of inquiry that could be undertaken, in order to fully test common assumptions about the way that legislation works, would be to interrogate the balance between prescription and discretion in statute law. That could be investigated using techniques of statutory interpretation, and potentially then replicated at scale using natural language processing.

How should we respond?

Legislative complexity might seem at first blush like a clear problem with a straightforward solution: to simplify legislation. But that is not the case. There is the practical question: how do we actually simplify legislation? There is the political question: can we simplify legislation without hindering Parliament’s ability to pursue complex policy goals? And there is the conceptual question, of whether the rule of law really requires that people be able to know the law — and whether that in turn requires that they be able to read legislation.

In some ways, the measures of complexity we have focused on are the most difficult to respond to. Some increase in word length could probably be explained on the basis that legislative drafters and policy makers have worked hard to spell out their proposals in clearer detail. And the speed with which legislation is amended could be a positive sign, that Parliament is actively monitoring the performance of its statutes and revising them to ensure they achieve their aims. However, that does not solve the basic problem, that all this legislation must be read by fallible human beings. And of course, Parliament is made up of people too. Most of them would lack the time and resources to carefully read and consider all the text that is enacted as law. No doubt, there are small groups within Parliament (e.g. committees) that do carefully scrutinise these texts — but they do not have constitutional authority to legislate. Some scholars have attempted to show how the understandings (or ‘intentions’) of these sub-groups can be said to belong to Parliament as an institution, but not everyone is persuaded.

There are also drafting practices that may make individual statutes far easier to navigate and understand — including those which the ALRC has outlined in its recently published interim report B. These are valuable proposals, but they may make but a small dent on the systemic problem of complexity. Ruhl and Salzman demonstrated the point with a metaphor: the simple maths sum, 2+2. This is easy to do. But it would take considerable time and effort to manually perform this sum thousands of times — and at some point, errors would occur. The task would be more difficult again, if the person had to continually check how many times the sum had to be performed. This is the challenge confronting the Australian legal system. Even if every statute were perfectly drafted, the sheer volume of legislation and the rate at which it changes would present a challenge. We can use some very basic metrics to try to understand that challenge. Scientific data suggests that adults silently read non-fiction texts at 238 words per minute. That means that in the form in which they were first enacted, this sample of 20 statutes would have taken the average adult around 120 hours to read. Today, the same 20 statutes would take almost 420 hours. But the mental capacities of human readers ‘are relatively fixed’.

Another potential solution lies in conceptual innovation, or revising the norms that we attach to legislation. This is — in the briefest outline — the path that some scholars have taken, in considering the implications of complex legislation for the rule of law. The rule of law is said to require, amongst other things, that people be able to know the law — which requires amongst other things that it is be accessible, comprehensible, and predictable. But Vincent Chiao argued that it is unrealistic to suppose that people can know the law in advance, and we should instead focus on their ability to challenge the legality of executive action after the fact.

This is an important consideration. But does legislative complexity not affect the performance of the courts, too? There are good reasons to suspect that complex legislation makes it harder for people to identify legal causes of action, and increases legal costs. And courts would seem practically incapable of reviewing but a tiny portion of the legislation that now exists, or the innumerable occasions on which that legislation is applied by the executive branch. At the very least, it would require free and ample access to legal aid, as John Tasioulas noted.

Is the solution, then, to embrace new technologies, that can augment the limited capacities of people to read and reason about the law? There is a growing body of literature, particularly in the US, that argues for precisely that. But this path is also fraught. The potential problems that arise when government relies on new technologies are well-known, particularly for Australian audiences all too familiar with disasters like robo-debt. One idea gaining traction is that of rules as code. This might be described as a technologically-driven approach to designing legislation. At its most ambitious, it involves co-creating legislation in natural language and machine-consumable form. Those machines could execute the legislation, but they could also generate information about it — in much the same way that the suites of ‘tools’ and ‘calculators’ provided on government departmental websites do today. And it is claimed that the results the machines produced will be more accurate, if the code they use is created at the same time as the underlying legislation, as this can avoid errors in ‘translation’. I and others have already questioned whether rules as code can really achieve that goal. Others have warned that rules as code would erode the rule of law in other ways, by destroying the flexibility and adaptivity that is inherent to ‘text-driven law’. Legislation has always been designed to be read by human beings, so designing it to be consumed by computers would lead public law into uncharted territory. But we may have no choice but to head in this direction, if we cannot reduce the complexity of legislation.

This post has only scratched the surface of the many important public law issues raised by contemporary legislation. If nothing else, we hope it shows that complexity is not just an issue for financial services lawyers, or tax lawyers, but for everyone interested in the way that our legal system functions, and its ability to sustain core values like the rule of law.

Dr Lisa Burton Crawford is an Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales.

Dr Elma Akand is a Data Scientist at UNSW Data Science Hub (uDASH).

Steefan Contractor is a machine learning research data scientist in the UNSW Data Science Hub, School of Mathematics and Statistics.

Dr Scott Sisson is Professor of Statistics at UNSW Sydney, and founding Director of the UNSW Data Science Hub.

—

Suggested citation: Lisa Burton Crawford, Elma Akand, Steefan Contractor and Scott Sisson, ‘Legislative complexity: what is it, how do we measure it, and why does it matter?' on AUSPUBLAW (23 November 2022)<https://auspublaw.org/blog/2022/11/legislative-complexity-what -is-it-how-do-we-measure-it-and-why-does-it-matter/>